Written by Elizabeth Barek

A climate series on the Polynesian communities and their cultures endangered by rising sea levels.

While corners of the world burn, other parts sink as Antarctica’s ice sheets melt at an average rate of approximately 146 billion tons per year alongside Greenland, losing 270 billion tons per year, according to NASA.

With the United Nations Chief warning that “global sea levels have risen faster since 1900, endangering nearly 900 million people in low-lying coastal areas”, it is hard to imagine how the communities of sinking islands are planning to preserve their livelihoods, traditions and languages in danger of descending with it.

One of those communities resides in the Pacific nation of Tuvalu. With a population of 11,204 as of 2021 (World Bank), the cheerful sounds of ‘Faatele’ and reams of colourful woven attire worn during their national sport ‘Te Ano’ are just a glimpse of the extensive culture and lessons the remaining Tuvaluans have to offer. The historical pots of culture, generational customs, religions and multitudes of uninscribed dialects will soon fade without a trace as Tuvalu expects to be one of the first countries in the world to disappear beneath the waves due to rising sea levels resulting from climate change.

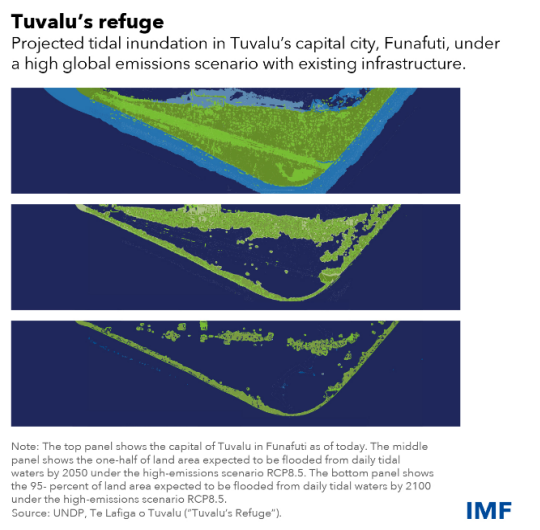

The frightening reality of a sinking capital

By 2100, 95% of the capital Funafuti will be flooded by high tides, as reported during the 27th annual UN Climate Change Conference in Egypt, making it ‘unhabitable’ by the time Gen Z reaches their 80s.

Photo of the changing landscape of Tuvalu’s capital, Funafuti. As sea levels continuously increase, more land is lost underwater. Photo by UNDP.

The alarming reality highlights the urgency to discover and document the Tuvaluan community and their traditions, which may not be around for much longer.

Why it matters

UN SDG 11.4 aims to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage”. While the main focus is on creating sustainable cities and communities, there is also the aspect of preserving cultural heritage, language and important landmarks. To maintain cultural diversity and ensure history and culture are not lost to climate change, documenting and archiving these endangered cultures and communities are vital ways of contributing to SDG 11.4. The alarming rate of climate change highlights the urgency to celebrate and showcase the Tuvaluan community and their traditions, which may not be around for much longer.

What is ‘Faatele’ and ‘Te Ano’?

Amidst the challenge, Tuvaluans remain resilient and united through two of their more well-known customs, ‘Te Ano’ and ‘Faatele’. ‘Te Ano’, literally translating to ‘the ball’, is the national sport of Tuvalu originating from the island. It is a highly paced and energetic team sport consisting of a captain and catcher facing each other on a playing field and batting two ‘ano’ between the teams to catch each other out. Traditionally played during celebrations such as Independence Day, the sport is popular in neighbouring islands such as Kiribati, another endangered island due to rising sea levels. After a game, they gather for ‘Faatele’, a traditional song and dance performance. ‘Faatele’ is usually performed during celebratory events such as weddings, visits from prominent leaders such as Queen Elizabeth II and other special dates. With the land loss caused by rising sea levels, few remaining locations in Tuvalu are suitable for hosting these large celebrations.

Two women sitting on the Funafuti airstrip in traditional attire after a game of ‘Te Ano’ by lens_pacific on

Instagram and photo of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip touring Tuvalu between 26th – 27th October 1982.

The Airstrip of Peace

One saving grace of Tuvalu is the Funafuti Airstrip, now the only extensive open space left in Tuvalu. When the sun sets, almost everyone in the country journeys to the Airstrip to engage in games, community activities and sports. It hallmarks the resilient community of Tuvalu that still enjoys the beautiful views from the ground. However, the fear lingers that someday, the Airstrip will become submerged underwater, making it impossible for anyone to leave. The Airstrip and the rest of Tuvalu, are threatened by high tides and constant cyclones. Few contingency plans aim to protect Tuvalu in their ways of life and their ancestral land.

What happens next?

There is a resounding absence of understanding about Tuvalu – its religious and cultural beliefs pre-colonisation, the historical significance of ancestral lands, the dialects across the islands, the impacts of practices such as blackbirding on Tuvaluans, and what it truly means to lose your homeland to the sea. The Tuvaluans are crucial in documenting and conveying the depth of these matters, especially as climate victims. Through their accounts and personal stories, I aim to gain an insight into the history and culture of Tuvalu by travelling using photojournalism, documentaries and long-form content. By shedding light on Tuvalu’s dilemma and other Polynesian islands, I hope to contribute to the conversation on climate change and urge countries like Australia to take more substantial steps to safeguard what remains of Tuvalu beyond their gain while keeping the essence of Tuvalu alive for future generations who will not be able to visit their ancestral land.